By Nadine Yousif and Eloïse Alanna, in Toronto and the Nass Valley

After almost a century and a journey of thousands of kilometers, an artifact recovered in Canada is now home. It is the first totem pole returned by a British museum to an indigenous community – a potentially unprecedented moment in the wider movement towards museum repatriation.

The museum curator, Marius Barbeau, had been eyeing the totem for some time.

It was the late 1920s, and the Canadian ethnographer had made numerous visits to the Ank’idaa village of the Nass Valley, an indigenous community nestled among picturesque mountains, streams and waterfalls in a remote region of British Columbia (BC).

There he photographed interesting objects and sent these photos to museums around the world.

One object in particular, the Ni’isjoohl memorial pole, caught the attention of the Royal Scottish Museum, now known as the National Museum of Scotland.

They offered him between CA$400 ($295; £240) for the pole – estimated at between CA$7,000 and CA$10,000 today – and Mr Barbeau accepted.

In the summer of 1929, when most Nisga’a were away working, hunting or fishing, he and his team simply took it.

The 11 m (36 foot) pole, carved largely from a single piece of red cedar, was commissioned to honor a warrior named Ts’wawit who died in battle.

After cutting the pole, Mr. Barbeau’s team bundled it onto a raft that floated down the river to Prince Rupert, on a journey that ultimately carried it more than 6,700 km (4,200 miles) to Edinburgh.

“We never gave him permission to steal our staff,” Amy Parent, whose great-great-grandmother commissioned it in 1855 to honor her warrior son, told the BBC.

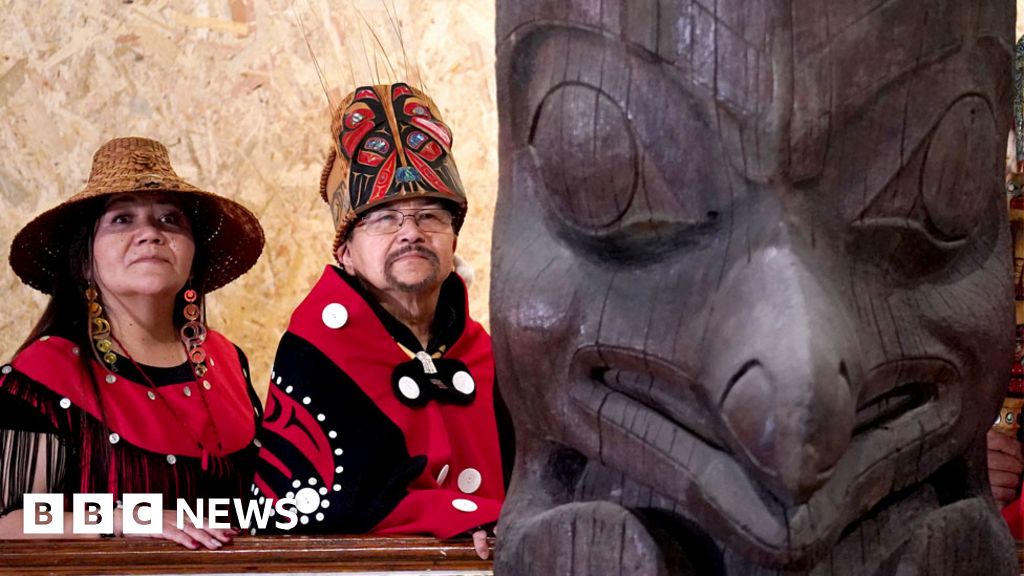

Now, nearly a century later, the Ni’isjoohl Memorial Pole is back in the Nass Valley, greeted by hundreds of people at an event marking its arrival Friday.

The pole will be on permanent display at the Nisga’a Museum, a modern building with a stunning glass facade and surrounded by snow-capped mountains.

PA Media

PA MediaUpon arrival, the foggy morning weather changed, leading to remarks about how the artifact was enjoying its first sunshine in a long time.

Children placed cedar branches around the pole as it rested on its side in the light, and people lined up to walk past and take photos.

It was a historic “repatriation” not only for Ms. Parent’s family, whose Nisga’a cultural name is Noxs Ts’aawit, but also for the Indigenous nation of about 600 people.

“It lays out what we can do for our families who know of other artifacts that may have been confiscated from their possession,” said Eva Clayton, president of the Nisga’a Nation.

The return of the Ni’isjoohl pole could also set a precedent in a broader repatriation movement that is gaining momentum around the world, as indigenous communities and nation states call on museums to return their objects.

The return journey

The quest to recover the flagpole began last year, when a delegation, including Ms Parent, visited the National Museum of Scotland to formally request its return.

Ms Parent told the BBC she felt emotional as soon as she entered the room where the pole was on display.

“As we walked up that escalator, we could feel the breath of our ancestors as we entered the Living Lands exhibit where the pole was,” she said.

The delegation explained to museum and government officials how the totem was recovered and demanded its return without any conditions.

During these conversations, Ms Parent said the delegation formed a deep connection with Scottish representatives over a shared history of colonialism and its impact.

By December, the museum and the Scottish Government knew what they were going to do. It was coming home.

“This is the place where the spiritual and cultural significance of the pole is most keenly felt, and it makes perfect sense that it is here with its residents,” said Chanté St Clair Inglis, head of community services. collections at the National Museum. from Scotland, who attended the welcome ceremony in British Columbia.

The mast began its month-long journey home this summer, beginning by being carefully removed from a museum window and transported by the Royal Canadian Air Force across the Atlantic to British Columbia.

It will be permanently housed within the Nisga’a Nation, where a place has been dug into the ground to symbolize a return to its roots.

Parent said community members will finally be able to learn the history of Ts’wawit and the significance of the artifact.

“We always wanted our children to be able to work less hard in order to understand the stories of who we are,” she said.

In Scotland, the national museum announced it would use the totem’s now-empty exhibition space to share the story of its return.

“It’s not about us losing anything,” Ms Inglis said. “It’s about developing a relationship and saying [the pole’s] history in a much better way.”

Is this the first in a long series of homecomings?

The return caught the attention of anthropologist and museum repatriation expert Chip Colwell.

Given its significance in Scotland and its importance to the Nisga’a Nation, returning home “is no small feat,” he said.

Mr. Colwell, based in the United States, said the connection has been forged between the Nisga’a Nation and the museum as part of this process “which creates new possibilities for what museums themselves can to do to repair the harms of colonialism.”

It’s also part of a broader shift within the museum community in recent decades, as countries and museums question how objects come into possession.

Many European museums have been resistant to demands for repatriation from indigenous peoples, he said. Now the door is open to the return of objects with great ritual or religious significance.

“We saw Indigenous people become very persuasive in convincing museums how important these objects were to them and how often they were being taken without consent,” Mr Colwell said.

Some countries – like France, for example – have also committed to returning looted treasures and objects, he added.

And he’s optimistic about it.

“The museum world and most societies have recognized the need for repatriation as part of what it means to be a 21st century museum,” he said.

For Canada’s Indigenous communities, these repatriation demands take on particular significance given the country’s historic policies aimed at erasing Indigenous language and culture – policies since considered a “cultural genocide”.

“The theft of their ritual objects was part of that process,” Mr Colwell said.

Being able to recover these objects, he added, “is fundamental to their survival as indigenous people.”

For the President of the Nisga’a Nation, the timing of the return of the Ni’isjoohl Memorial Pole made the event all the more significant as it took place on the weekend that Canada marks National Peace Day. truth and reconciliation. It was created to recognize the harms of colonialism and the residential school system, where Indigenous children were taken from their homes and enrolled in boarding schools in an attempt to assimilate them.

Clayton, herself a residential school survivor, said the return of the pole appears to be a form of reconciliation in itself.

“What Scotland have done is an incredible and kind gesture which will go a long way to healing the wounds.”

“Unapologetic travel lover. Friendly web nerd. Typical creator. Lifelong bacon fanatic. Devoted food enthusiast. Wannabe tv maven.”

:strip_icc():format(jpeg)/kly-media-production/medias/4889148/original/004013400_1720683504-firman_1.jpg)